In preclinical oncology, researchers face a familiar tension: how to capture reliable, longitudinal tumor data without relying on invasive procedures like biopsies or euthanasia.

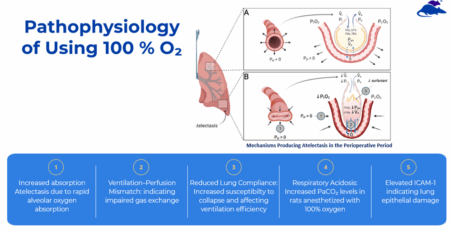

These traditional methods often require larger animal cohorts, introduce variability, and provide only single-time-point insights, limiting understanding of tumor progression (Goyal et al., 2018).

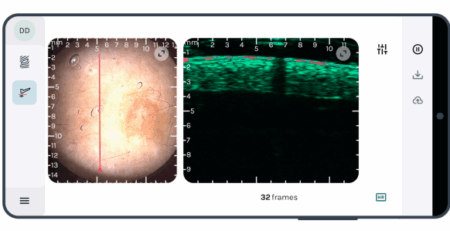

The new SkinScanner, a high-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) system with Doppler imaging, addresses these issues by enabling noninvasive tumor monitoring, particularly for non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC) like basal cell carcinoma (BCC), improving both data quality and animal welfare.

Why Noninvasive Methods Matter in Cancer Studies

Traditional preclinical cancer models often involve:

- Using more animals to capture data at different time points.

- Single snapshots of tumor biology, missing longitudinal changes.

- Biopsies or sampling that can disrupt tumor biology (Goyal et al., 2018)..

These approaches can yield fragmented data, increase variability, and raise ethical concerns.

On the other hand as a non-invasive imaging system, SkinScanner allows researchers to collect multiple data points from the same animal, reducing animal use while using fewer animals overall and generating richer, longitudinal datasets (Raszewska-Famielec et al., 2020).

The SkinScanner Advantage

The SkinScanner operates at 20-40 MHz, ≤10 mm depth providing high-resolution imaging of tumor size and structure in live animals with penetration depths up to 10 mm and a field of view of 10 mm (depth) x 12 mm (lateral), optimized for preclinical models like mice.

This approach offers several benefits:

- Track tumor growth and structural changes over time in the same subject.

- Reduce or eliminate the need for repeated biopsies, minimizing disruption to tumor biology.

- Enhances data consistency by enabling standardized, longitudinal imaging (Li et al., 2025).

- Aligns with the 3Rs principles (replace, reduce, refine) by reducing animal use without compromising study quality.

For labs focused on both scientific rigor, the 3Rs principles of animal research (replace, reduce, refine), and looking to adhere to international standards of care in the use of lab animals, SkinScanner represents a practical step forward.

It’s important to note that HFUS requires skilled operational laboratory procedures for definitive diagnosis and imaging (Bobadilla et al., 2018).

How Labs Can Start Integrating Noninvasive Imaging

Transitioning to noninvasive imaging like SkinScanner for cancer research is straightforward and can enhance existing workflows. Making the shift doesn’t require an overhaul of your research program.

Labs looking to incorporate noninvasive imaging tech like SkinScanner can:

- Adding refinement tools like SkinScanner to complement existing workflows.

- Replacing select biopsies with imaging to monitor tumor progression.

- Standardizing imaging protocols to improve reproducibility across studies.

- Collaborating across teams to integrate imaging data with in vitro or computational approaches or AI-driven image analysis for comprehensive tumor characterization (Bobadilla et al., 2018).

These steps can reduce variability, enhance data quality, and align with ethical research practices.

The Takeaway

Noninvasive imaging technologies like the SkinScanner allow preclinical oncology researchers to collect longitudinal data on NMSC, such as BCC, with high-resolution HFUS.

By reducing reliance on more invasive procedures, labs can generate consistent, high-quality data while using fewer animals, better aligning with the 3Rs principles. Though operator skill is required, the SkinScanner offers a practical, scientifically grounded solution for advancing preclinical studies.Kent Scientific supports researchers in adopting noninvasive imaging into their programs—so that you can trust in your data quality and focus on impactful discoveries.

References

- Bobadilla, C., et al. (2018). Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 32(12), 2095–2105.

- Goyal, K., et al. (2018). Brachytherapy, 17(3), 547–552.

- Li, Y., et al. (2025). Dermatologic Surgery, 51(2), 234–242.

- Raszewska-Famielec, M., et al. (2020). Skin Research and Technology, 26(4), 512–519.